The Myth of Solid Ground: a synopsis

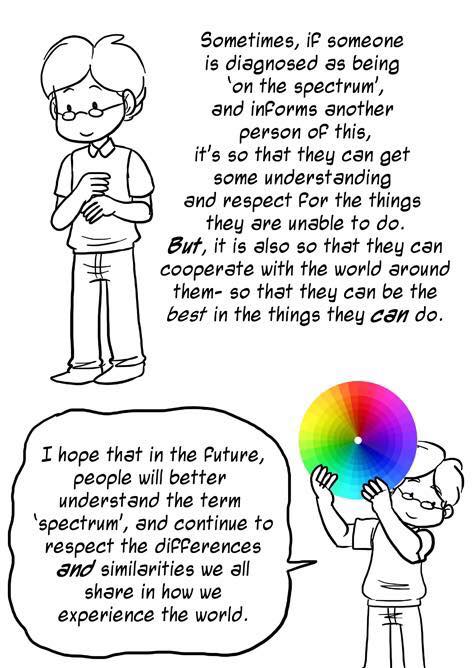

My aim was this: to write the book I longed to read back then, some twenty-five years ago, when Hannah was first diagnosed. There was no internet then, not like now, and the few autism books I could find fit into one of two genres: dry medical texts and anecdotal “miracle memoirs.”

The medical texts worked hard, with their studies and statistics, to mask the fact that science knew (and knows) little more about autism than I did (and do). I couldn’t have discerned that fact back then, of course—and, who knows?—maybe I wouldn’t have wanted to discern it, then. When disaster happens, after all, the first thing you long for, once you can breathe again, is rescue, which, unless you believe in magic or God, would seem to require human expertise. By spending Hannah’s first three years thinking everything was just fine, I’d handily proven my own incompetence. No wonder I deferred, then, to doctors with clipboards, who, with one word, replaced the daughter I thought I knew by heart with an inscrutable enigma: an alien, a machine, an aggregate of symptoms and “behaviors.”

No wonder, too: the rise of the miracle memoir. These books, most of them written by parents who’d fallen through the same dark fissure that had trapped my family, countered the bleak forecasts of medical texts with warm, human stories of hard-won victory.

For this was the era we lived in then. We were, at long last, past the nightmarish age when we spoke of “refrigerator mothers” whose everyday remoteness forced their children into hiding inside stony, silent fortresses of the mind. No, by 1991, the year of Hannah’s diagnosis, we no longer believed that mothers caused autism. What we believed, instead, was that mothers could cure it.

The method of the miracle varied from book to book. Some parents cured their children through a dramatic change in diet, some by megavitamin supplements. Auditory Integration Therapy did the trick for a few kids, while other parents swore by facilitated communication, or chelation therapy, or the magical powers of hyperbaric chambers. Some parents rescued their children via sixteen-hours-a-day, one-on-one behavioral therapy. Several children simply cured themselves, through tireless, undaunted acts of will.

“Can Autism Be Cured?” was the title of a Woman’s Day article my mother sent me in 1994, but by then I already knew the answer, which wasn’t just “Yes,” but “Of course!” The article’s tagline says it all: “From birth this zombie-like girl seemed hopelessly unreachable. Then a simple two-week treatment turned her into a normal young woman.” (And even as I type it out again, that last, triumphant sentence breaks my heart, just a little, one more time.)

For this was what hope looked like in those days, in the era of the hard-earned miracle. The bright half of a false duality, hope rose from a desperate parent’s denial of despair. For me it was a torturous up-and-down cycle–a runaway merry-go-round I finally had to leap off, mid-whirl. I had to learn, through the course of years, to believe in neither thing—not despair, but not hope either. By now, in fact, some ten years gone since Hannah died, I seem able to engage with the world only as it presents itself right now, with whatever might be tangible or provable or present. It’s my life’s deepest lesson, so far—this surrender to the starkly here and now. And it was Hannah who taught it to me.

She never spoke to me, of course–not even in my dreams. Nor does she speak nowadays, but neither, of course, does she need to. Timeless, now, in picture frames and in my heart and mind, she grins, forever my laughing Buddha, and I’m starting, I think, to know what she means. Or perhaps what I realize is that she doesn’t mean anything, she just is, and that’s the point. But I’m getting ahead of my story.

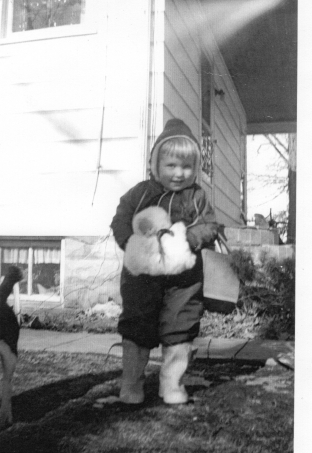

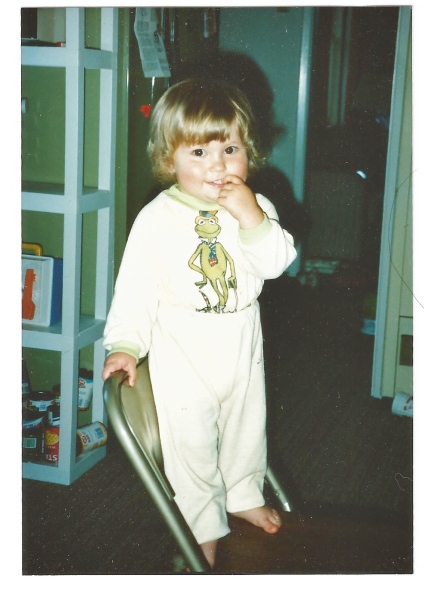

Hannah was born in 1988, to clueless parents who nonetheless thought themselves clever. Trapped already in the fierce and ridiculous melodrama of our marriage, surely Henry and I had neither right nor reason to enlist a third actor. Yet, oh, how deeply into love I fell, when Hannah joined the play. How I studied her—how she and I studied each other. How small the world beyond ourselves became. How quickly her joy became, for me, the only joy that mattered.

As I write in the book: “In our early days—those first three, pre-diagnosis years—Hannah seemed, if not exactly transparent, at least no less knowable than anyone else in my life. Indeed, I believed—and perhaps it’s even somehow true—that she was the person I knew best, back then, and that I played that part for her too. We were the centers of each other’s tiny worlds–yet so often I can’t remember that anymore. I tend to think, no, no, it was mainly my breast she wanted. Whatever else, who knew? And there’s something true-ish about this, in the sense that Hannah and I lived primally—like primates, I mean–in those days. The baby gorilla, as she suckles, gazes up at her mother’s eyes. The mother gazes back. In this brief moment, which will somehow last forever, they are mutually enthralled. This is love.”

How often, in the hard years of Hannah’s growing up, did I worry that that bond of love had broken, or—much worse—that it had never been “real” in the first place. Yet time after time, through the course of years, if I paid close attention, I’d glimpse that bond again.

Again, from the book: “I think gently of an early Sunday morning in the fall of 2003, when Hannah left the house in only her nightshirt, and raced away down the street. I quickly followed her, in my own nightgown and slippers, to her favorite park a block away. The day was warm enough for me to perch atop a picnic table there, pondering the anatomy of acorns, as meanwhile Hannah reeled, in her old rubber swing, from sky to sky. When at last she was ready to return to the house, she nonetheless held back, frustrated, stiff, at the edge of the grass, and I remember, as well as any fine moment that day, the thrill I felt when, at last, I guessed the reason: that the nuts and pebbles dappling the sidewalk and street, hurt the tender bottoms of her feet. I sit here thinking of that moment again, wondering if I can ever explain the joy I felt: the miracle, the bliss of discovering, at last, a problem I could actually solve. I took off my slippers and put them on Hannah’s feet. She laughed—elated as if by a magic trick—and, happily, agreeably, we walked each other home.”

Yet my daughter’s life was turbulent, from the beginning. What’s more—this is an autism memoir, after all—it got harder and harder as time went on. Yes, and suddenly I find myself wanting just to leave you right here–to say, as politely as possible, “You want details? Read the book.” Because I honestly don’t want to tell it again—no, not the merest example or detail. Because that’s why you write a book, isn’t it, so that you can close it, afterwards, and never have to say another word?

One way of seeing our lives in those days: as one long and rarely interrupted state of emergency. Though I hardly knew this at the time, Hannah was what people call a “difficult” baby: fitful, sleepless, often wailing, for reasons that were hard to figure out. She nursed till she was five. She didn’t sleep through the night till she was six (and dosed with Trazodone). Moreover, and increasingly as she grew up, Hannah had bouts of what seemed to be an intense internal pain that no one who worked with her could ever understand, much less alleviate. She banged her head against walls, she bit her own hands, she shrieked and howled, sometimes for hours at a time. Soon she began to turn her frustration toward the people trying to help her—she rushed at us headlong, pinched and bit and rammed her head against us, bent our fingers back, strangled us from the back seat of the car. Her rages grew more dangerous as she grew older and stronger. The toughest times return to me, today, in vivid flashes: locked inside the bathroom, I sit on the floor, bracing my back against the flimsy door as Hannah hurls herself against it from the hallway. The wood arches inward, a wind-billowed sail. Knowing how soon it might fracture, I scan the room for something I might use to deter attack. Shall I throw a towel over her head? Or fling a dixie-cup’s worth of water in her face? If I sprayed air freshener at Hannah, would it hurt her eyes? Would it even slow her down? Would it only enrage her more?

But if this were the full story, I’d hardly have bothered to write it, because any parent who needs to know such harsh particulars has already learned them, with no need for anecdotal reminder. I’ve met so many of these parents by now. Our lives have intersected in support groups, conferences, blogs, real life. Together we form a beautiful, fallible, self-lacerating tribe. By our trembling hands, our haunted eyes, our facial tics, we recognize each other.

Hannah’s rages (if that’s what they were, and not merely what they looked like) reflected only part of her. To know my daughter fully, you had to see beyond your own bruises, and even then, the crazy truth would take you by surprise and you’d believe it only fleetingly. Only once the play ended—when, abruptly, at seventeen, Hannah died of an epileptic seizure in her sleep—and you suddenly had enough quiet (too quiet!) time to think, only then might you grasp the truth you’d only glimpsed before: that all this time you’d been seeing your life upside-down. In your role as Hannah’s teacher, you’d been miscast: you were meant, instead, to play her faithful, if slow-witted, student. As I write in the letter that forms the last chapter of The Myth of Solid Ground:

“It’s amazing, Hannah: your effect on people. What drew them in every time—it wasn’t pity. No, you seduced us instead with what I want to call—don’t laugh—a rare charisma. Do you get what I mean? You startled us all, and kept us startled for years, with the stark purity of your innocence. No matter the moment, you were guileless, sinless, unsulliable–as fully exempt from corruption as the Virgin Mary. No wonder we loved you so dearly. No wonder we took pride in our scars. No wonder we couldn’t help but become, around you, like those ancient tribesmen who’d have regarded you as a spirit guide, a shaman, a gift.”

When I started writing The Myth of Solid Ground, I felt so cockily sure that this wouldn’t be another “miracle memoir.” And now that it’s finished, imagine my chagrin—and my wonder, my dizzy relief–to find that Hannah’s story overbrims with miracle, from start to finish. But how was I to know this, way back then?

I sought to write the book I’d longed to read in those hard days—the book that would tell the bare-knuckle truth, let me bear witness, help me heal. And here, to my amazement, it is.